Alberto Marnetto's Notebook

Note: the patch is available at the end of the article (HERE). This post is about its making-of.

Stunt Island is a flight simulator from the year 1992. You can read more about it in my previous post.

Last month I finally beat the game, winning all the missions and getting the title of “Stuntman of the year”. While I was replaying the videos of my attempts, as well as some fan-made SI films in the channel, I wondered if I could somehow mitigate the obvious limitations of the rendering engine.

Also, I was always fascinated by the art of reverse engineering, and I thought this could be a good opportunity to learn something in this field. Assembly is not new to me, but dealing with an archaic DOS program, working without gdb’s features and any kind of debug symbols means entering an entirely different world.

I spent a dozen of hours learning the tools of the trade and trying to figure out the puzzle, and I was very happy of my eventual success. After finding and patching the right location in the executable, the engine got some extra horsepower. No extra resolution unfortunately, but many more details, as one can see in the comparisons below.

For a video comparison, one can check out this “remaster” of the movie Mickey’s Revenge, courtesy of Doug Armknecht’s Stunt Island Central channel.

In the following, I’ll show the process and some failed tries. Even if this is far from being a professional effort, I hope that publishing this can be of help to other learners, or maybe induce some experts to chime in and suggest improvements (in the name of Cunningham’s Law). Tutorials about debugging with DOSBox are rare to find, so I feel that even this small example can be useful.

Also, I hope to revive some interest in an old, but beautiful and unique game.

Since I have never debugged DOS programs, the first step is to build up the toolset. I need

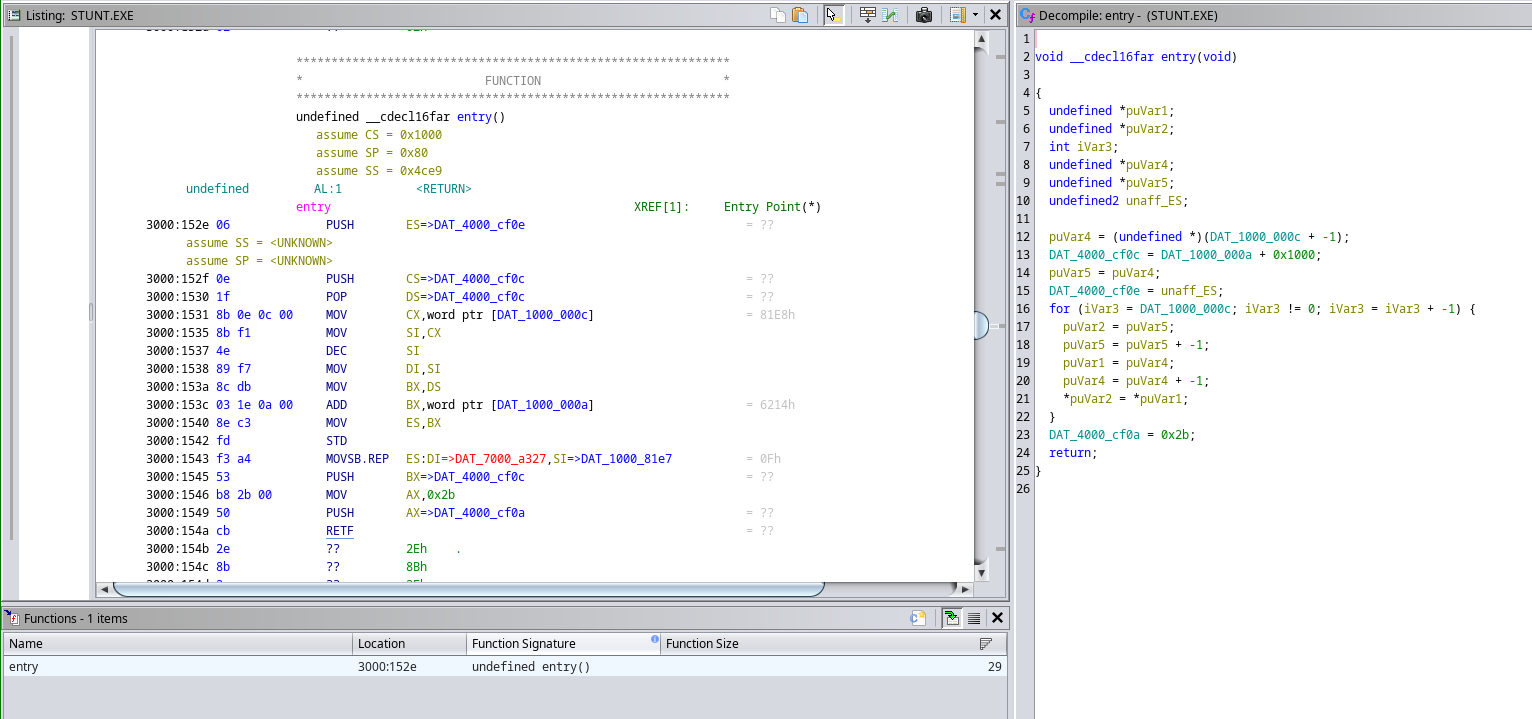

I start by opening the game executable in Ghidra. The first result is underwhelming:

Just one function and a lot of non-decompiled bytes, that does not look good. Maybe the decompile process failed?

Let’s look at the function. I cannot grasp all the details, but it seems to be copying a buffer. This rings a bell – I remember reading some articles about self-decrypting executables. Could it be that the real game code is obfuscated and only revealed after the startup?

By the way, what does the file header look like?

$ hexdump -C STUNT.EXE | head -5

00000000 4d 5a 18 00 0d 01 00 00 02 00 20 1c ff ff e9 3c |MZ........ ....<|

00000010 80 00 00 00 0e 00 52 21 1c 00 00 00 4c 5a 39 31 |......R!....LZ91|

00000020 ff 3f e8 64 00 a3 12 62 89 16 14 62 e8 81 00 3b |.?.d...b...b...;|

00000030 3e ec f9 75 04 3b 06 ef 76 1b ea fd c7 ff 0f 06 |>..u.;..v.......|

00000040 1c 62 00 00 b4 43 cd 67 84 e4 75 37 4f 87 ee 16 |.b...C.g..u7O...|

Seeing the “LZ91” finally clicks for me. This game was probably compressed by some variant of the Lempel-Ziv algorithm. Some googling leads me first to this article by Sam Russell and then to the UNLZEXE unpacker. Turns out that the original compression tool was authored by the prolific genius Fabrice Bellard.

OK, let’s decompress the executable and reload it in Ghidra:

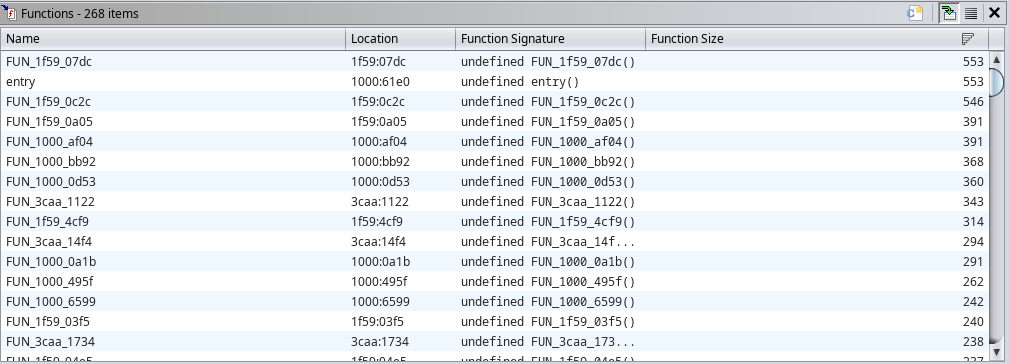

Looks better. Can we make any sense of the functions?

Nope, this is over my paygrade. But we are in 2024, maybe we can seek the help of a LLM? Copilot says:

This looks like assembly code mixed with some higher-level C code constructs, dealing with system-level operations. Here’s a bit of a breakdown:

* Initial Setup: The function begins by initializing variables and handling some immediate checks and adjustments.

* Comparisons and Bit Manipulations: It checks some global variables and performs bit shifts and comparisons to adjust the control flow based on these conditions.

* System Calls: There are several system interrupt calls, likely interacting with hardware or the operating system.

* Function Calls: The code calls other functions (like FUN_1f59_36f7, FUN_1f59_0bc2, and FUN_1f59_0c2c) which perform some specific tasks.

* Loops: The code includes loops and conditional checks to perform repeated tasks or to continue execution based on certain conditions.

* The main flow is about handling and manipulating certain global variables and possibly hardware states, based on the names and types used. However, without more context on these global variables and the overall program architecture, it's tough to pin down the exact purpose.

Oh, I see, “the code calls other functions which perform some specific tasks”. Awesome. Thanks all the same, AI. See you in some years, and let’s rely on carbon-based intelligence in the meanwhile.

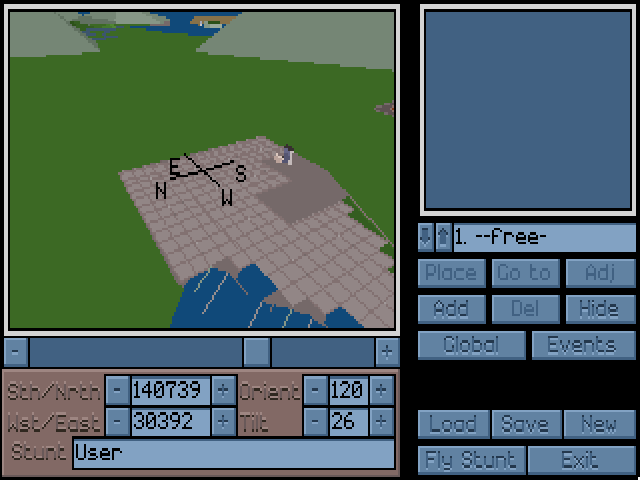

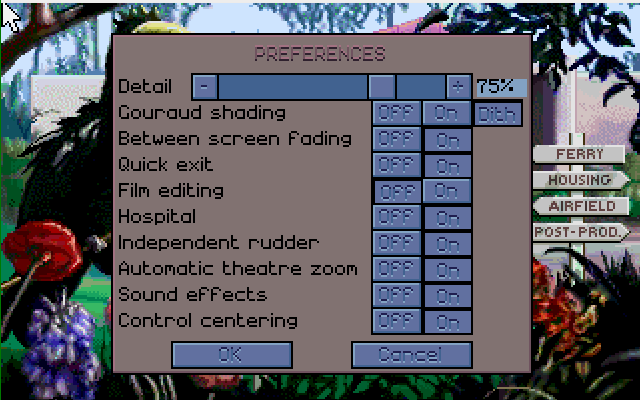

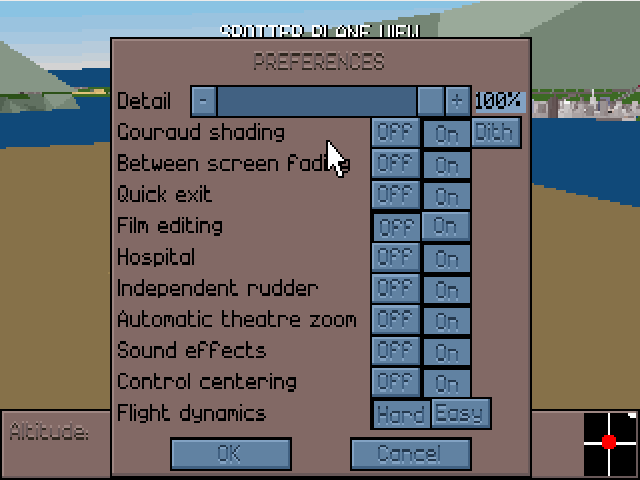

The static analysis has not yielded any result yet, but I have another idea. Stunt Island has a “Detail” setting:

My hope is to find out where the detail level (here, 75%) is stored in the memory, and to change it to 255, or to see how it is used in the rendering process.

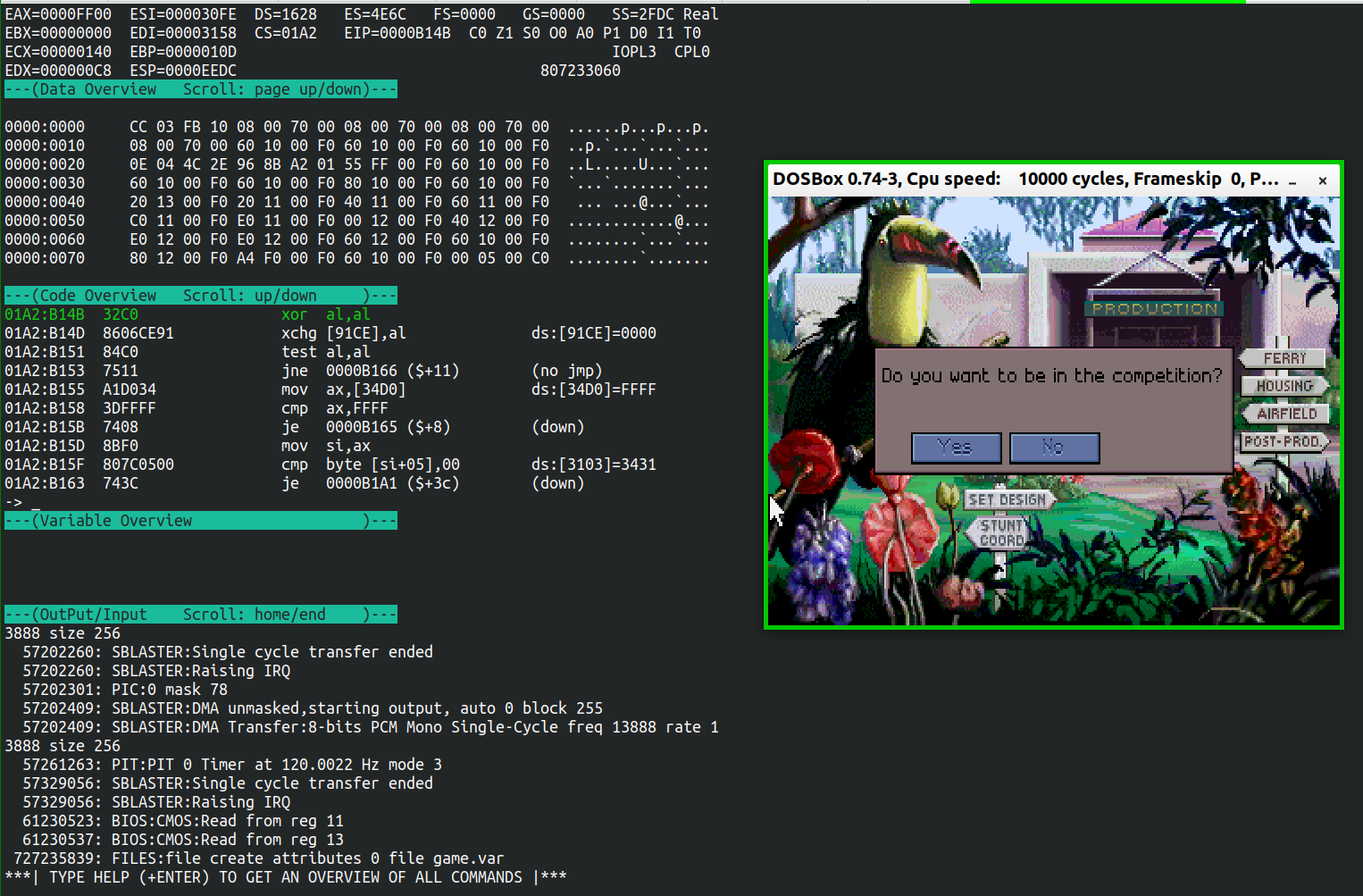

Let’s fire up Dosbox debug. The best manual for the interface is a thread on the Vogons forum.

The GUI is nice, even if I miss the amenities of modern debugging, especially the function names. However, credit is due to the authors: they put in nice features like a branch predictor that shows whether a jump instruction will be taken, and in which direction (back or forward), assuming that the current status of registries and memory stays the same.

How to find the location of the detail level variable? I navigate again to the “Preferences” screen and spend a lot of time there, trying to devise a method to extract such information. My list of failed attempts includes:

BPINT 16) and press “Return” with the mouse pointing on the “plus” sign. The program breaks in a input-reading routine, but stepping through the code I lose my way before being able to understand what the program is doing. Considering I could be in the middle of a complex UI-drawing routine, I give up.bpmem a1000:3500). Again, I cannot find the way out of the graphics code."%u%%"): nothing foundWhile looking for other ideas, I find a nice list of techniques by the makers of ScummVM. One of the options is “File Access”, which reminds me that the game must store its preferences somewhere. A quick search by date reveals that a file with the promising name GAME.VAR is updated every time I alter the settings. Let’s see how it changes when a different detail level is chosen. At 99% detail we have

$ hexdump -C GAME.VAR

00000000 70 fd ff 01 ff ff ff ff ff ff 99 e7 0b 00 38 01 |p.............8.|

00000010 64 02 0b 00 57 01 64 02 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |d...W.d.........|

00000020 00 00 00 |...|

00000023

Now let’s set 1% detail:

$ hexdump -C GAME.VAR

00000000 8f 02 ff 01 ff ff ff ff ff ff 99 e7 0b 00 38 01 |..............8.|

00000010 64 02 0b 00 57 01 64 02 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |d...W.d.........|

00000020 00 00 00 |...|

00000023

So the detail level is in the very first two bytes. Unluckily, it seems already to be scaled, with 100% = 0xffff. No chance to simply set it higher. But let’s not lose hope so soon: we have now more information to find out where in the memory this value is stored, and maybe we can change something else in the 3D computations.

I need a breakpoint when GAME.SAV is written. According to an old but practical guide to the interrupt table, a file write is triggered by calling interrupt 21h with 40h in registry AH. Dosbox can set a breakpoint on precisely this event:

I change the detail level, close the preferences window and, bingo! Breakpoint triggered.

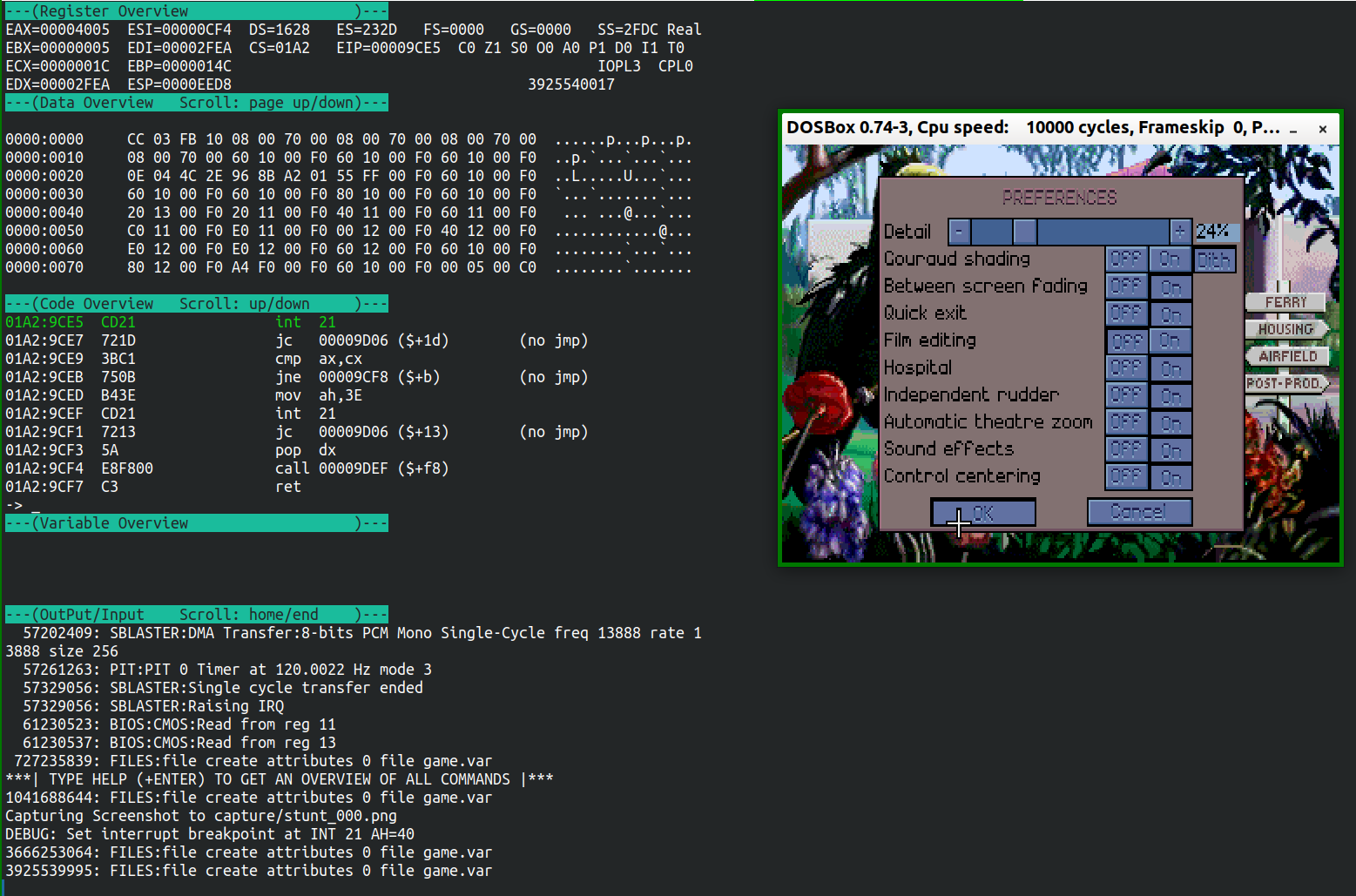

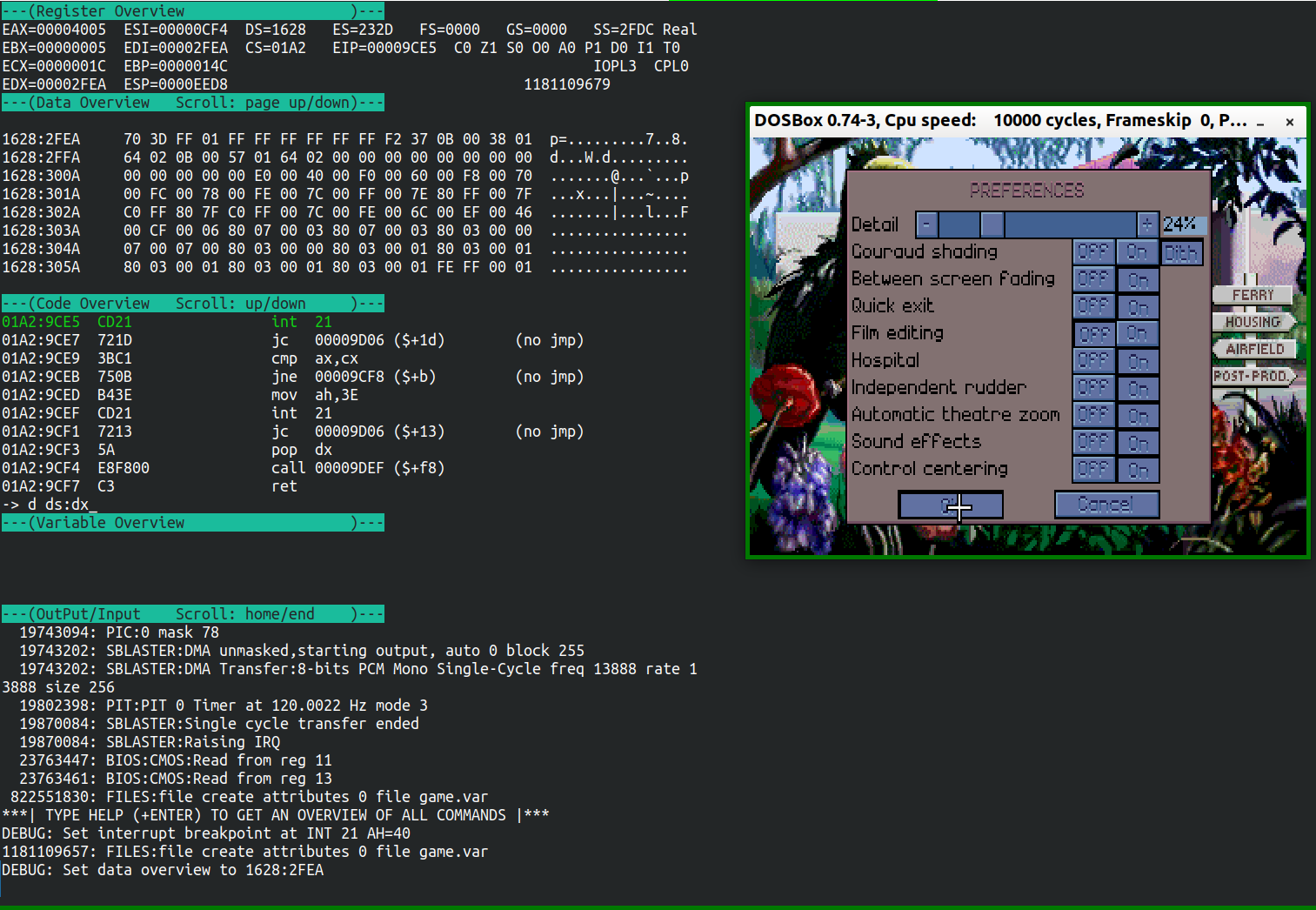

The bytes to write are in DS:DX, so 1628:2FEA. Let’s have a look:

Yes, the 16-bit value at that address matches the detail level I set (0x3d70/0xffff ~= 0.24). I bet that this is a global variable and will stay there for the whole duration of the program, what I verify by starting a mission:

The value is still there. Very nice.

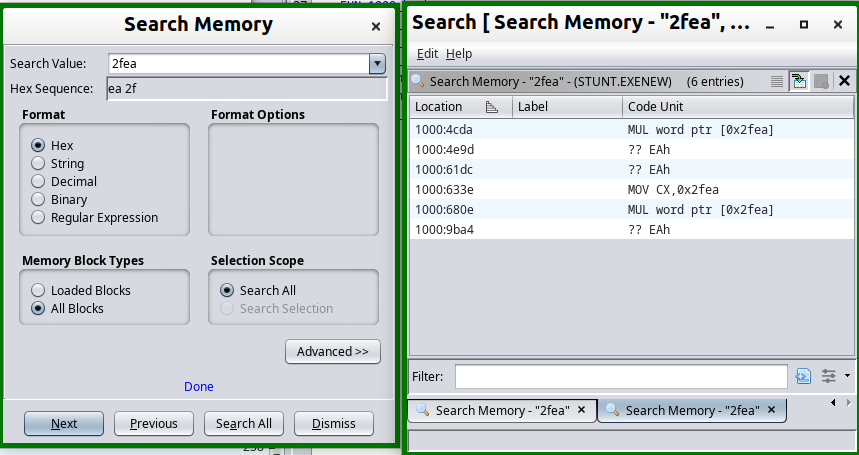

Now I have to see where this variable is used. Let’s go back to Ghidra, and look for the low two bytes.

I am lucky, not too many occurences.

First location: CS:4CDA. Ghidra decompiles the code to

*(int *)0xb86 =

(int)((ulong)*(uint *)0x2fea * 100 >> 0x10) + *(int *)0xa5a +

(uint)((int)((ulong)*(uint *)0x2fea * 100) < 0);

Not super clear, but the meaning becomes evident when I set a breakpoint there (BP CS:4CD8): the line is executed only when I open the preferences box. So the “100” in the code must be part of the rescaling to a percentage.

Second location: CS:680E. The assembly is clearer than the C equivalent:

1000:6809 a1 ea 91 MOV AX,[0x91ea]

1000:680c f7 26 ea 2f MUL word ptr [0x2fea]

1000:6810 d1 e0 SHL AX,0x1

1000:6812 d1 d2 RCL DX,0x1

1000:6814 89 16 f2 91 MOV word ptr [0x91f2],DX

So, the variable at DS:91EA get multiplied by the detail level, and then written at DS:91F2. No idea what DS:91EA is, though. I first think that this routine is calculating some per-polygon quantity, but it turns out that it is only run once per frame. Also, when I run some frames in mission 1 the variable at DS:91EA switches between 0x0999 and 0x7FFF. Let’s ignore the matter: we now know that at DS:91F2 something gets written that is proportional to the detail level. Moreover, with Detail set at 100% this variable is often set at 0xFFFD, almost the maximum.

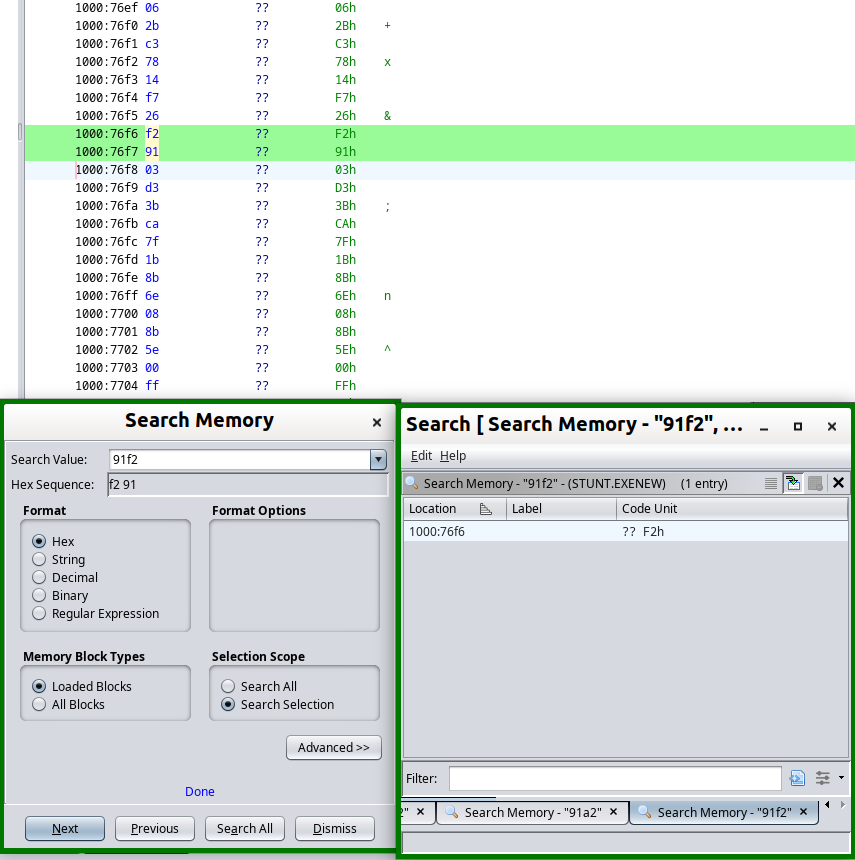

I look for f2 91 in Ghidra: it only yields two occurrences. One is the fragment we just analyzed, the other is in the middle of some bytes that Ghidra did not decompile automatically.

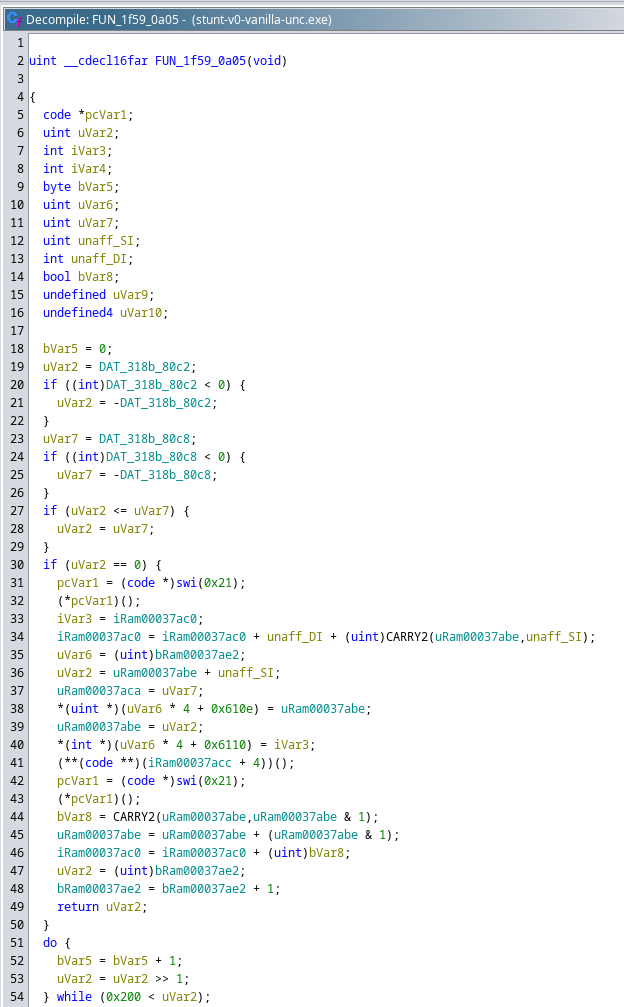

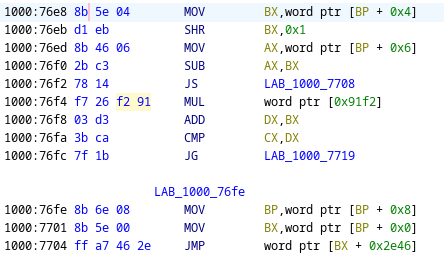

Well, there is no other place to look, so I ask Ghidra to decompile this section. Some attempts later, a plausible assembly appears:

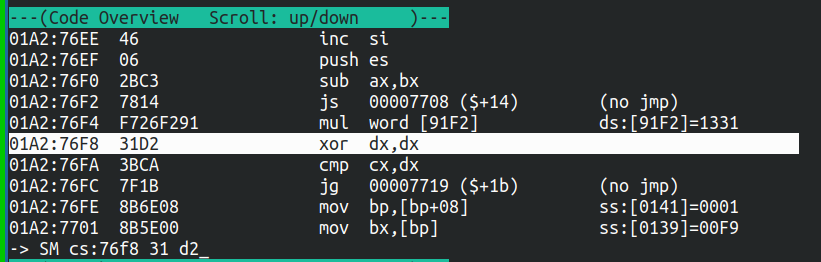

I ensure that the decompilation is right by setting a breakpoint at the start of the fragment (BP CS:76E8), and for added safety I verify that the program counter (EIP) really points to the locations shown in the listing. This code gets executed many, many times per frame – have I finally reached the goal?

Let’s try to understand the code: first it decrements AX and executes what follows only if it’s still positive. Not sure what this means but some live debugging shows that the condition is met quite often anyway. The following calculation is easier to understand: in the x86 architecture, calling MUL multiplies AX by the operand, leaving the result in DX:AX. With maximum detail, we know that DS:91F2 will be set at 0xFFFD, so that the multiplication becomes almost a 16-bit left shift, setting DX to (AX_old - 1). The lower the detail, the lower DX will be. Then the code executes the following branch only if CX <= DX + BX, otherwise it gets skipped.

In an interview by Fabien Sanglard, Stunt Island’s main programmer Adrian Stephens revealed an important aspect of the rendering engine: each 3D entity in the game is represented as a tree, and the game decides whether to render the (coarser) top nodes or the (finer) lower levels according to their distance from the observer. And we see here that a subroutine gets executed if CX is under a certain threshold, which gets bigger the bigger is the detail level. Let’s make the bold hypothesis that CX is the object distance, and (DX + BX) determines the distance threshold under which a higher-resolution model gets loaded.

I can test the hypothesis by overwriting the calculation with new code. Let’s start by setting the threshold to zero. Ghidra shows which bytes to insert:

I can do that in the live program:

The experiment works perfectly: all details disappear, Jackson City is reduced to flatland.

But what I want is the contrary: changing the code so that the max resolution gets used for all objects. Let’s just set the threshold to the max:

SM cs:76f4 c7 c2 ff 7f 66 90

(MOV DX, 0x7FFF ; NOP)

This makes the engine totally unresponsive to the keyboard commands. I guess I was too greedy. My second try is more modest:

SM cs:76f4 c7 c2 ff 4f 66 90

(MOV DX, 0x4FFF ; NOP)

And here we are: Stunt Island in the best detail you’ll ever get in a 320x200 window! Pity that the system is still just barely responsive: even with DOSBox’s CPU set to max performance, I cannot control my plane, and this is the best screenshot I am able to take before crashing.

But there is a better way to go sightseeing: the rendering routine is shared across flight sim, video player and set designer, and at least in the last mode I can take all the time I need to steer the camera. It takes some minutes to push the extremely sluggish control, but after a while I can frame Jackson City and surroundings, looking more gorgeous than ever!

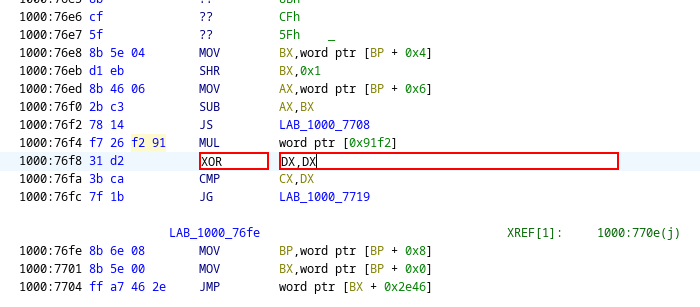

Now that I explored the limits, it’s time to turn back the dial and find some compromise to make the game playable. The current patch is brutal, it just uses a fixed threshold ignoring the original value in DX. We know that DX is approximately AX_old * (detail_level/100), maxing out at AX_old - 1 if the detail level is 100%. What about putting a multiple of AX there? The space is limited, only 6 bytes, but a bitshift is compact enough. After some experiments, I settle on

89 c2 c1 MOV DX,AX

e2 03 SHL DX,0x3

90 NOP

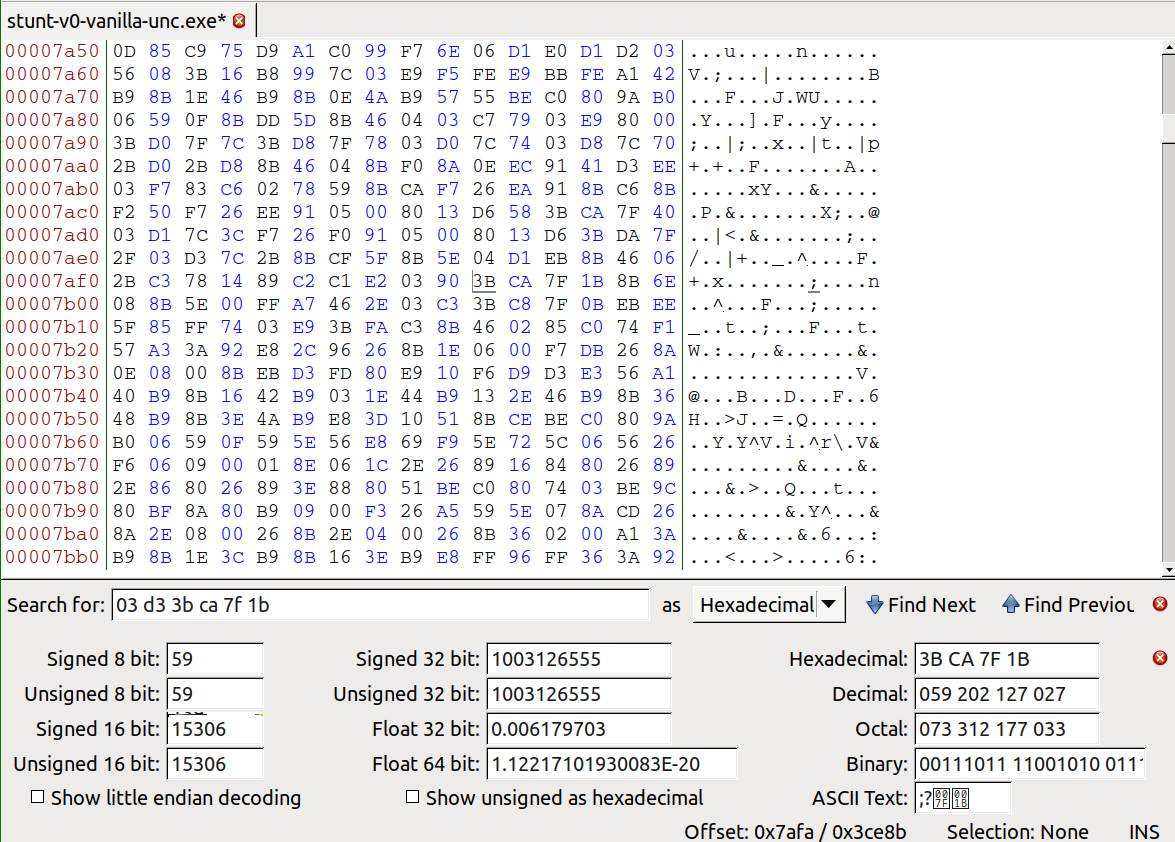

which would be the equivalent of a 800% detail. I patch it in using the Dosbox command:

SM cs:76f4 89 c2 c1 e2 03 90

And everything goes as hoped: the quality is great and the game (after cranking up Dosbox’s CPU to the max) runs quite fluidly. Time to celebrate!

By the way, the fact that the three most significant bits of DX are discarded does not seem to lead to any noticeable glitch; I could add some code checking for overflow and saturating the value, but this would require more bytes than I am replacing. I might create the algorithm elsewhere and then JMP to it, but at the price of making the code slower and the patching process more difficult. The current version is simple and good enough for me, and after all one must leave some fun to future tinkerers.

Before calling it a day, I still have some housework to do.

First, I need to edit the executables to avoid having to live-patch the code every time. Stunt Island provides not only the game executable (STUNT.EXE), but also a video encoder and a player (MAKEONE and PLAYONE), so that users can distribute and view their films without having to navigate through the game interface. To do a complete work, I want to patch all these files.

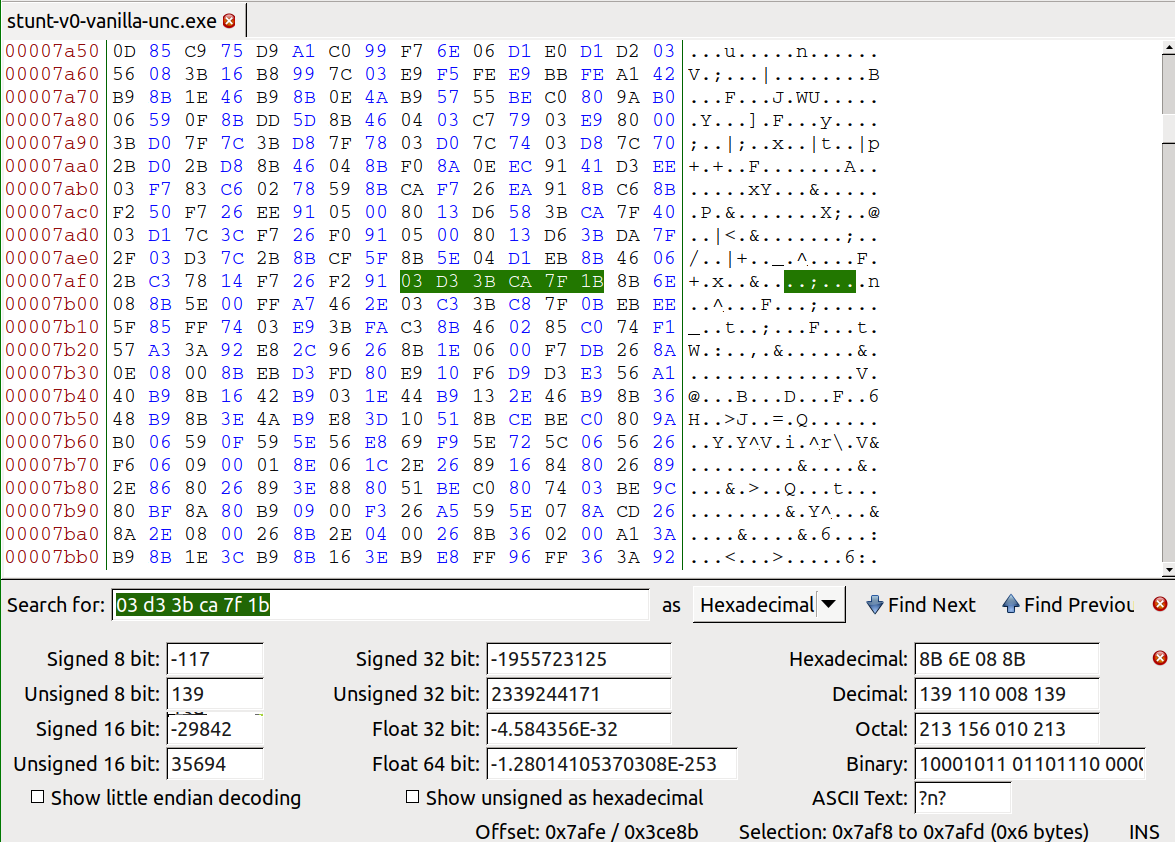

Fortunately, the rendering code is the same in all three executables. However, the detail variable is stored at different addresses, so the assembly is not the same. The easiest way to find the relevant location is to search for the instructions that follow the MUL (so the ADD / CMP / JG sequence): they only refer to register values, so their encoding (03 D3 3B CA 7F 1B) is the same in all the files to patch.

Then, we move four bytes back, and we replace the “multiply by the detail level” segment (F7 26 XX XX 03 D3) with the “multiply by 8” code (89 C2 C1 E2 03 90).

The operation works well on all three executables. The patched PLAYONE can only play films created by the patched MAKEONE, but this seems reasonable. I guess that the films created by the vanilla MAKEONE are missing the high-polygon versions of the far objects.

Second, I must create a patching program that can upgrade the game without embedding Disney’s code. It would be nice to just implement it as simple search and replace for the six bytes that need to be overwriten, but unfortunately there is the problem of the LZ compression. I cannot bundle unlzexe, whose copyright status is unclear, so I end up recompressing the patched executable and diffing it with the unpatched version. The compression smears my 3-byte change all over the file creating a big diff, but this seems to me the least worst method. The patcher then applies the diff to the original game file, which must be provided by the user. This should put the patch on the safe side, copyright-wise.

Finally, I am informed that Disney released a patch (“#3”) containing some features like an alternative beginner-friendly flight model. It would be good if the 800% mod also worked on this version. Luckily the renderer was not changed so the same patching method can be used. The only surprise happens when uncompressing the new .EXE: it turns that the compression method was slightly changed (from LZ091 to LZ091E), and unlzexe does not recognize the format. However, the algorithm is the same, just the magic number used for the format identification has changed. Commenting out the magic number check in the source code of unlzexe solves the problem: I can uncompress the file and create a patch using the same process of the original game.

So, here the best Stunt Island one can have, with the enhanced rendering engine and the quality-of-life improvements of Disney’s patch:

To play the “definitive” version of Stunt Island, three steps are needed:

stunt-islandNote: some antivirus software will incorrectly flag si-8x.exe as malware. It is a false positive – I would not put my name under a virus, after all. You can also examine the patch’s source code and build it on your machine.