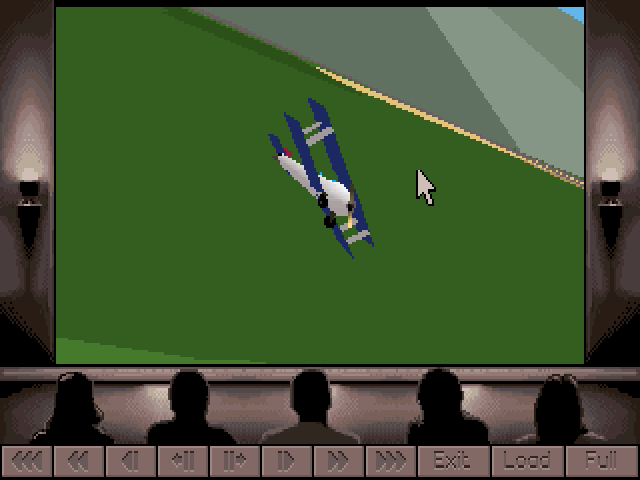

Here we fly a 1908's June Bug

Alberto Marnetto's Notebook

What is Stunt island?

For Wikipedia, it is a “Stunt Flying and Filming Simulation”, designed by Adrian Stephens and Ronald J. Fortier and published by Disney in 1992.

For me, Stunt Island is a tragedy.

A small tragedy, for sure. Nobody got directly harmed by the game, unless they tried to revive in real life some of the missions. But I find it quite sad to see how much of the potential of this work got wasted.

True to its promise, Stunt Island gives the player the possibility to be both a plane stuntman and a filmmaker.

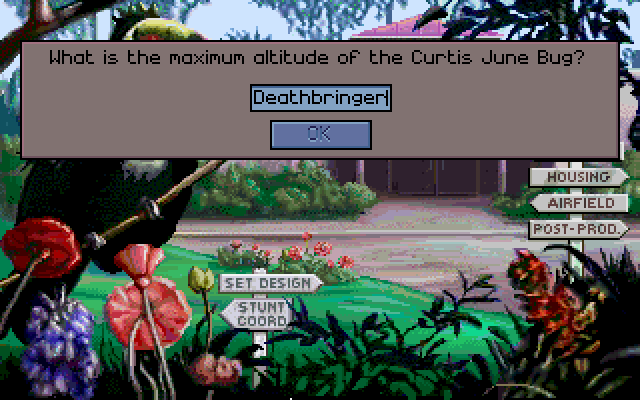

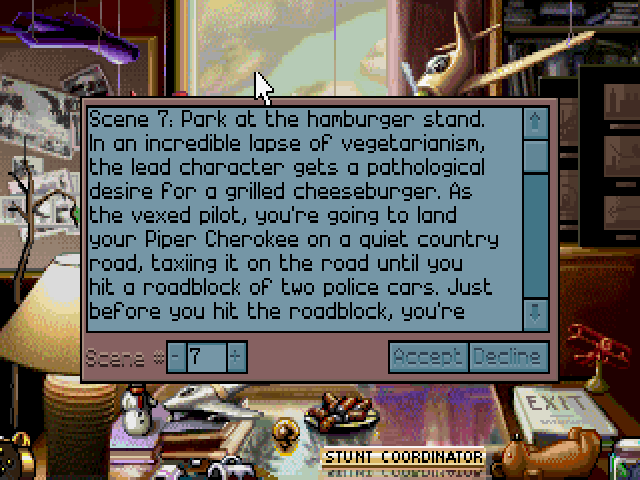

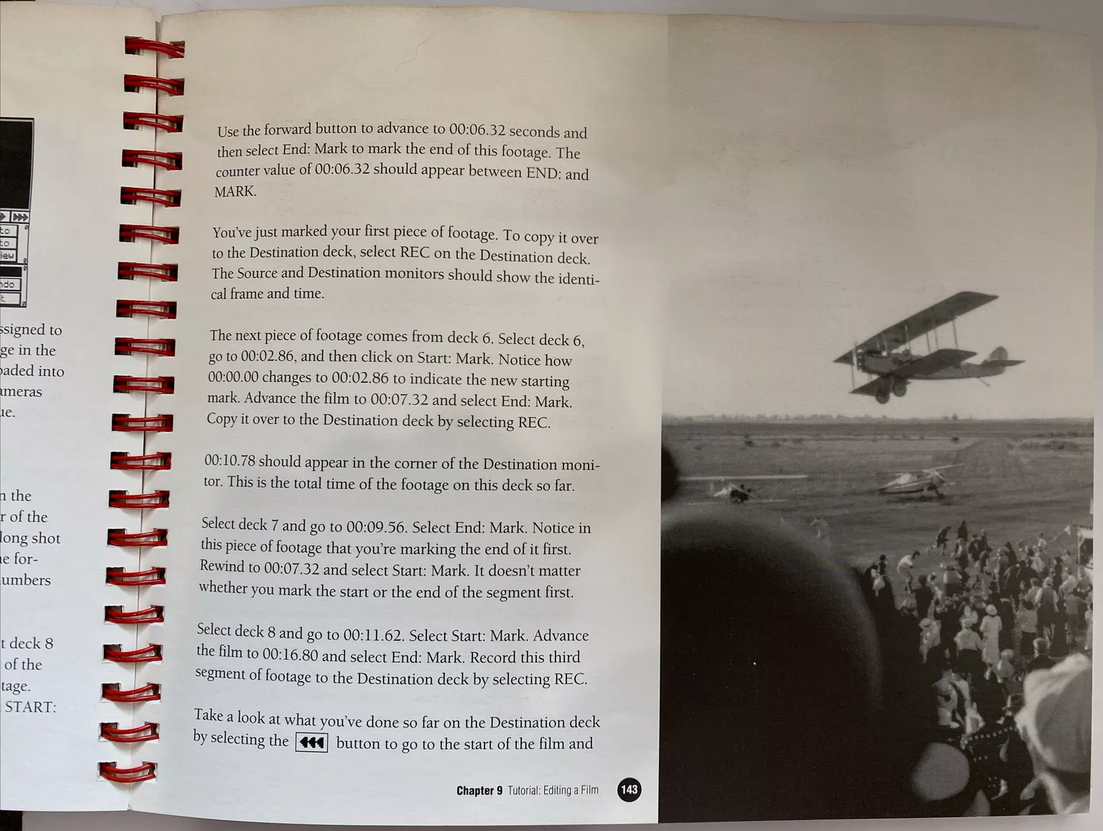

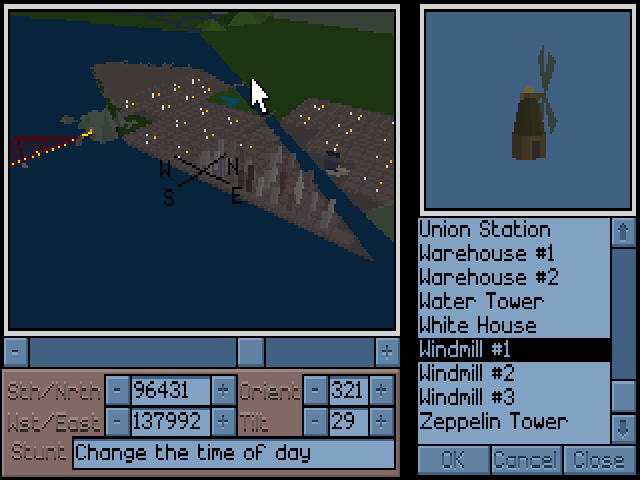

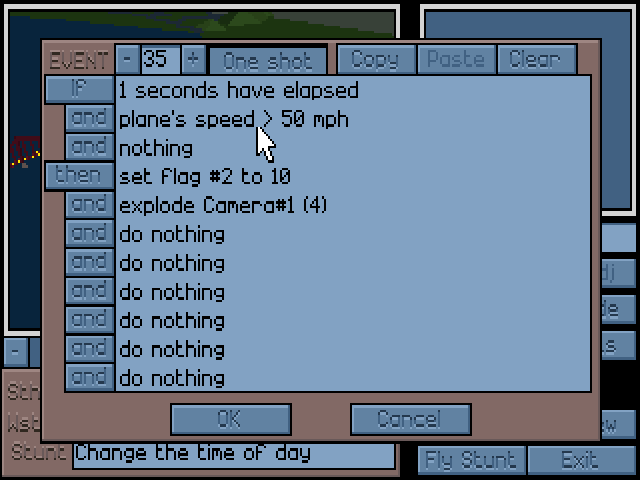

As stuntman, one can pilot an aircraft plane in 32 dangerous flying scenes, either as individual missions or in the context of a tournament. One can also create new stunts in a sophisticated set design tool. As filmmaker, one can use the same set designer to create any kind of film scene, regardless whether for an action-filled plane movie or a indoor psychological thriller. Choose the setting, place cameras, position actors and scenery, use the integrated scripting language to make all entites move and interact. Then head to the post-production room and piece together the footage in a film.

The amount of content provided was great for a game of that era: more than 40 “flyables” (mostly planes, but fancier choices like a pterodactyl), hundreds of various assets, plus the eponymous island, with many square kilometers of low-poly terrain, including various cities, mountains, a dam and several other locations.

The 3D engine was a marvel, bug-free and very fast even on low-end machines, yet offering rich scenarios and a decent flight model. Sure, other flight simulators of the era has similar features, but most of them were the result of years of iterations. Stunt Island instead was written from scratch, in less than two years, by a tiny team who also had to implement the huge filmmaking part. Stephens & Co. still found the time to add Gouraud shading, a novelty for the time.

This is only a glimpse of what the game had to offer. Other reviews can surely do the game more justice; I recommend PC Gamer’s 2012 retrospective.

It’s hard for me to understand why this game failed to leave a mark in the videogame history.

For sure, the publisher did not help: Disney did not particularly believe in the game. In an interview by Fabien Sanglard, the designer Adrian Stephens confirmed that Disney lost interest in the product as they decided to focus exclusively on games based on their own intellectual property. There were plans to release some expansion packs with new assets, and even a sequel, but they were soon abandoned.

This basically sealed the fate of could have been a promising series. The Nineties were a time where a 3-year-old game was already outdated due to the extremely rapid pace of the PC hardware improvements, and flight simulations were one of the genres that most needed state-of-the-art graphics to be marketable. With its 300x200 graphics, Stunt Island rapidly become obsolete, and with no updates emerging, it slowly faded from many gamers’ memory.

The “movie director” soul of the game had a better destiny that its flight simulation part. After all, Stunt Island was one of the extremely few videogames to allow users to create their own artistic works. Many years before terms like “machinima” and “content creator” entered the vocabulary, the set designer and the scripting language of the game offered a unique opportunity for wannabe filmmakers to transform their ideas into a real video. Disney was also generous enough to provide a freeware player, so that anyone was free to distribute their videos to their friends or online.

Some fans of the game also formed a club called SIFA (Stunt Island Filmmakers’ Association) to share ideas, filming tips and distribute videos. The group was quite active for about a decade, steadily producing videos and experimenting with increasingly sophisticated techniques. They also managed to contact Stephens, who gifted them the asset editor Disney used to create the props. With this tool in hand, a lot more became possible. A tribute to Star Wars (“Truck Wars”) was bound to happen, but many other works were produced, and I’d encourage the reader to check them out on Youtube.

However, even the creative community slowly moved on to other tools, some of its members even graduating to professional filmmaking. The flow of films and support materials seems to dry out around 2000, and the community discussion channels (Yahoo Groups, Geocities) went mostly lost with the shutdown of their hosting channels, as they never migrated to newer platforms.

Stunt Island is still remembered, but it has not (yet?) been blessed by a nostalgia-fueled revival. Other games of the era enjoy small but active fan communities, producing a new content at a steady pace: for example, as of November 2024, Broderbund’s Stunts has a tournament currently running on the dedicated fan site ZakStunts, and the modding community for the original Prince of Persia has at least six maps released since the start of the year (published at popot.org).

For Stunt Island, the reference sites are two: Stunt Island Central by Doug Armknecht and Stunt Island Harbor by Mic Healey. I absolutely encourage to reader to pay them a visit. Both curators are collecting materials related to the game, both official files or content produced by the fan community. Mr. Armknecht is also curating a Youtube channel, which publishes community-made videos and own creations, including a freshly-made full walkthrough of the missions. Yet, the sites are mostly a museum for a game that was: new content is still occasionally produced occasionally, but most updates come from the rediscovery of old material.

Other well-known retrogaming places do not improve the outlook. GameFAQs has no guide for the game. Jimmy Maher’s blog (“The Digital Antiquarian”) does not cover it. The Wikipedia page only offers minimal information. No speedrun is to be found. Aside from the two sites I mentioned, the most valuable modern tribute to the game is probably Fabien Sanglard’s interview with Adrian Stephens, offering a wealth of information about the game’s making-of and even some technical details about the rendering engine. Nothing comparable to Sanglard’s monumental dissections of ID Software’s masterworks, but still a precious glimpse in the machinery running behind the scenes.

Well, I really hope that this game gets rediscovered. Retrogaming is fashionable today, and Stunt Island still has much to offer to gamers and creatives alike. It would be nice to see some speedruns of the missions, some fan-made mission pack, or maybe a AI-generated film.

Or maybe, by some miracle, Disney could decide to release the source code and allow us to see how the 3D engine worked. Given the amount of “Doom on a toaster” variants, I am quite sure that someone would find creative ways to play with the code, and maybe finally let it break free from its 320x200 resolution.

To end this post on a positive note, playing Stunt Island today is easier than ever: you can just grab a copy on GOG or Steam for pennies. At Stunt Island Central or Stunt Island Harbor you can download the “P3 patch” to add some features and bugfixes. And if you want a modern touch, you can apply my own 8x detail patch to get much improved graphics.